Oxytocin versus Pitocin®: Induction of Labor in Different Worlds - Part 2 of 3

The ARRIVE Trial, rising induction rates, and when an induction might actually be reasonable.

Part 1 of this series focused on oxytocin and its activities throughout the pregnancy continuum. In Part 2, I will be focusing on the increased use of synthetic oxytocin (Pitocin®) in the conventional, hospital-based maternity care model. Part 3 will focus on the potential detrimental effects of the nearly ubiquitous use of Pitocin® in U.S.-based childbirth, considering that 98% or more of births are happening within hospitals.

Part 2

Induction of labor is so hot right now…

Given oxytocin’s potent influences on the uterine myometrium in childbirth, exogenous synthetic oxytocin, which goes by the brand name Pitocin®, seemed like a really great means by which to control childbirth, an otherwise untamable expression of the divine feminine, in all her glory.

IOL is occurring at a rate of about 30% in the United States. Augmentation of labor has also increased, and most women are going to receive at least a whiff of Pitocin® if they give birth in the hospital, whether for the purpose of “getting things going”, “speeding things up”, or minimizing blood loss immediately after birth.

Both induction and augmentation rely largely on the use of Pitocin®, and these interventions are not wholly beneficial to mothers and their babies:

Babies are being born at odd hours of the night. Presumably Pitocin® is used less during standard working hours, and perhaps night shift personnel are being incentivized to crank out babies during the nighttime to “open the rooms” for the oncoming day shift.

Babies are being born at earlier gestational ages in the United States compared to other developed nations, an obvious issue when comparing gestational age of newborns born at home compared to those born in the hospital, where Pitocin® is passed out more generously than candy on Halloween.

Postpartum hemorrhage rates are increasing, and a well-known etiology of postpartum hemorrhage is prolonged exposure to Pitocin®, among other interventions.

Cesarean rates have been increasing for decades, and inappropriate induction and even overly-aggressive augmentation likely play a role.

Pitocin® is nearly ubiquitously used in maternity care units

IOL in the U.S. has been on the rise for decades, but we saw a sharp increase after publication of the ARRIVE Trial.

The ARRIVE Trial was a multi-center, placebo-controlled trial, and the results were published in 2018 in the NEJM. The researchers offered a trial of expectant management versus IOL to 22,533 eligible women (low-risk, nulliparous). The 3062 women who agreed to participate were randomly assigned at 38 weeks 0 days to: a) labor induction between 39 weeks 0 days and 39 weeks 4 days or b) to expectant management. The primary outcome was a composite of perinatal death or severe neonatal complications; the principal secondary outcome was cesarean delivery.

The authors concluded that “IOL at 39 weeks in low-risk nulliparous women did not result in a significantly lower frequency of a composite adverse perinatal outcome, but it did result in a significantly lower frequency of cesarean delivery.”

Important insight #1 - The change in risk of c-section was 3.6% in favor of induction (18.6% versus 22.2%). Pause. The c-section rates in both the IOL and expectant management groups were well-below the average c-section rate in our country. Authors of the study also found that women who underwent IOL (versus expectant management) at the beginning of the study had a lower risk of developing a hypertensive disorder.

Important insight #2 - Timing of induction was initiated based on bishop score, rather than started at 39 weeks carte blanche.

Of note, the Bishop score was first published in 1964 by Edward Bishop and included cervical dilation/effacement/position/consistency along with fetal station. From the study, Dr. Bishop himself recommended against induction for any nulliparous woman even with a “favorable” cervix due to the unpredictability of nulliparous labor.

The modified Bishop score was adopted in 1976, and this included the subtraction of a point for nulliparous women and added a point for each previous vaginal birth.

The ARRIVE Trial only looked at nulliparous women, and they didn’t use a modified Bishop score. Other studies also did a poor job of accounting for parity.

Important insight #3 - The protocol for induction was not uniform. Every OBGYN in the world has a different approach to cervical ripening, and every L&D nurse is going to differ slightly in their attention to and adjustment of the Pitocin® infusion rate.

Important insight #4 - The fact that 33% of eligible women declined to participate is important because a woman’s confidence in her autonomous choice based on her beliefs, values, and her appreciation of risks, benefits, and alternatives can make or break their childbirth experience (and chances of vaginal birth). We can’t continue to lean on a 4% reduction in c-sections as a justification to offer induction to all-comers around 39 weeks gestation as they did in the ARRIVE Trial.

Important insight #5 - There is a myriad of variables influencing the decision of an individual practitioner to recommend and proceed with cesarean section while a woman is in labor - whether induced or spontaneous.

Individual management of induction has a huge influence on whether IOL will result in cesarean or vaginal birth.

In fact, in a massive 2020 study conducted by the CMQCC looking at nearly 1,000,000 births in across nearly every hospital in California, cesarean rate after induction of nulliparous, low-risk pregnancies ranged from 18.5 to 84.6% depending on the physician, even after risk adjustment. Significant variation was also seen across hospitals.

As Milo Chavira, MD, FACOG, one of my earliest mentors, stated in a recent presentation for Intentional Birth with regards to the likelihood of cesarean section: “The relationship between IOL and cesarean section is fairly complex and nuanced.”

Important insight #6 - We still aren’t entirely sure how labor begins, and many researchers looking at labor curves, for example, have admitted that determining when a woman enters the latent phase of labor (early labor) is often improbable if not impossible.

My wife, for example, was nearly fully dilated prior to feeling obvious uterine contractions in both of her vaginal births.

Important insight #7 - We can’t discount the influence of the Hawthorne effect on the outcomes of these types of studies in obstetrics.

Were Pitocin® infusion rates more carefully adjusted by the nurses so as not to impart fetal distress on fetal heart rate monitoring?

Was the additional attention from the clinicians to women and their partners giving birth while enrolled in the trial ultimately helpful in easing their nervous systems, which might allow labor to unfold in a relatively natural way?

Were clinicians more patient with early labor than they would have been otherwise had their center not been enrolled in the trial?

Was more time permitted during the 2nd stage (pushing) for those in the induction group?

The authors don’t fully address these obvious confounders, and that’s ok, because it’s only one trial, albeit a multi-center “RCT”.

One study to rule them all

Before and after the ARRIVE trial, a number of RCTs were published in search of an association between IOL and cesarean section rates. Some were congruent with ARRIVE, but others came to quite the opposite conclusion to that of the ARRIVE authors. Each of the following found an increased risk of c-section when a low-risk, nulliparous pregnant woman is induced:

Seyb, 1999, 1561 births, cohort: aOR 1.89

Also worthy of mention: OR 4.66 if an epidural was placed when cervix was <4 cm dilated

Ehrenthal, 2010, ~25,000 births, retrospective cohort: aOR 1.93;

Considering a myriad of variables, the authors perceived that induction contributed directly to about 20% of the c-sections in this cohort.

Vardo, 2011, 485 births, retrospective cohort: aOR 1.8

Researchers also reported higher rates of epidural, postpartum hemorrhage, pediatric delivery attendance and neonatal oxygen requirement and longer hospital stay with induction.

Butler, 2024: 640,191 births, retrospective cohort: aOR 1.23, 1.31, 1.42 and 1.43 when induced at 38, 39, 40, and 41 weeks, respectively

**An odds ratio of 1.8 suggests an 80% greater chance of having a c-section than vaginal birth, as an example.

Meta-analyses of trials examining labor induction versus expectant management conducted prior to the ARRIVE Trial found little if any benefit of early induction, so inducing at 39 weeks without medical indication was considered heresy before ARRIVE. And there have been a number of studies going back and forth on this topic ever since.

Since the publication of the ARRIVE Trial in 2018, however, average induction rates, particularly this new “39 week induction”, have increased nationwide. One study of 13 hospitals across the U.S. found that IOL rates increased by 6.7% without a significant change in cesarean rates when comparing data before and after the ARRIVE Trial was published in 2018. Other follow-up studies suggest that the ARRIVE data is generalizable and that adoption of early induction at 39 weeks may lead to a decrease in c-section rates over time.

How scientific is it to change our practice so dramatically in response to a single study? Rhetorical. No need to respond.

Oh, and by the way, a cost-effectiveness analysis found that universal adoption of early IOL at 39 weeks would be associated with an additional annual $2 billion price tag to our already costly healthcare system. If for no other reason, could we save money by advocating for the onset of spontaneous labor?

Is c-section all that we care about?

Our myopic reliance on the ARRIVE Trial to justify early inductions permits us to ignore the lived experience of so many maternity unit clinicians who know that when Pitocin® is used improperly and when we aren’t patient enough with the unfolding of the rite of passage that is childbirth, a number of detrimental effects might be observed.

When physicians and L&D nurses aren’t contributing to a data set that could drastically change obstetrics practice, they operate a little differently. When they’re left to their own devices, we know that there are a variety of factors that influence rates of intervention in childbirth, namely the decision to proceed with cesarean birth. Spong et al, through their famous paper from 2012 that was published in hopes of decreasing primary c-sections, highlighted that failed IOL, second-stage arrest, first-stage arrest diagnoses, and non-reassuring fetal heart rate, were the reason for 10%, 10-25%, 15-30%, and 10% of primary cesarean sections, respectively.

This goes back to my takeaways from the ARRIVE Trial…

And what about the hidden costs to women who undergo a multiple day induction only to find themselves in the operating room, where they have a much greater chance of losing a lot of blood and having to stay in the hospital for days on end?

A study of 55,000 women from 2005 found that, indeed, IOL and augmentation of labor with Pitocin® were both independently associated with increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage (OR of 1.4 for both). But people prefer to look at smaller studies which support their hopes that they won’t have to admit that prolonged exposure to Pitocin® may lead to postpartum hemorrhage.

Hear me out: Your personal comforts have little role in the delivery of maternity care.

You are welcome to cherry-pick the “evidence” in any way that you wish to support your internal bias. We all do this, and this is a primary concern in the practice of medicine, particularly in childbirth.

We must be discerning in how we apply clinical trials to our practice.

The bottom line on ARRIVE

Evidence-based medicine has three legs. The first is derived from peer-reviewed literature, and ideally multi-center, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. The second is client preference, values, and history. And the third is clinician experience.

Anybody who has worked on a maternity unit has experienced the process of eliciting informed consent from pregnant women around IOL and cesarean section. It’s done poorly at best and often borders on coercion.

Hospital staff nod along when they hear that a woman induced for non-medical reasons at 39 weeks ended up in the operating room after a long induction. They also nod along with the reality that many surgeons move women to the operating room for lack of patience or for fear of looking “lazy” in the eyes of oncoming physicians who will be assuming care of women who are “taking too long” to give birth.

We all have experienced these circumstances first-hand. And sometimes peer-reviewed literature conflicts with our direct experience, because there are simply too many variables to control any study perfectly.

Neither the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) nor the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine (SMFM) honor this trend towards earlier induction without consideration of a myriad of circumstances that might be important in counseling a woman around the risks and benefits of induction.

Per Practice Bulletin #107, Induction of Labor (Note: this document has been removed from their clinical library as of September 2025):

“Indications for induction of labor are not absolute but should take into account maternal and fetal conditions, gestational age, cervical status, and other factors.”

- ACOG, 2024

Per the Obstetric Consensus Statement from SMFM for the prevention of primary cesarean:

“Before 41 0/7 wks of gestation, induction of labor generally should be performed based on maternal and fetal medical indications.”

- SMFM, 2010

ACOG then goes on to list examples of scenarios in which IOL might be indicated, including chorioamnionitis, fetal demise, placental abruption, and others, including, post-term pregnancy, implying 42 weeks gestation or later.

Not 41 weeks. Not 40 weeks. Not 39 weeks. But 42 weeks.

Is IOL right for me?

As we’ve already explored, there is a lot of nuance around IOL. While I am an advocate for decreasing the rates of IOL, there are still plenty of reasons in which IOL may ultimately benefit mothers and babies. Indeed, sometimes it can be a life-saving recommendation.

Here are a few common reasons given for evacuating a baby out of their amniotic universe:

Small babies:

When fundal height is less than expected (midwives) or estimated fetal weight is lagging on ultrasound evaluation (doctors), this may suggest fetal growth restriction and a greater chance of fetal death unless birth is expedited through induction or cesarean.

The only means we have to ascertain the potential etiology for a small baby is to look at large datasets across certain demographics, whereby we can compare the growth of a baby against others babies of similar gestational age.

Sometimes babies are small because of their genetics. In this case, they often start small but continue to grow consistently throughout pregnancy but remain smaller than most. This can be due to small parents (constitutionally small), or it can be due to aneuploidies and other chromosomal abnormalities. Others can be small due to infection. A full assessment with a critical eye is required to make an educated guess.

Other times babies are growing on par with other babies but then suddenly they start to fall behind. These are the babies that often benefit most from early birth. The first thought is placental insufficiency, whereby the placenta simply isn’t able to supply the oxygen and other nutrients to the growing fetus as pregnancy progresses. This is often accompanied by gradual decreases in amniotic fluid around the baby, and it is sometimes associated with a hypertensive disorder or occult bleeding behind the placenta, a condition known as placental abruption.

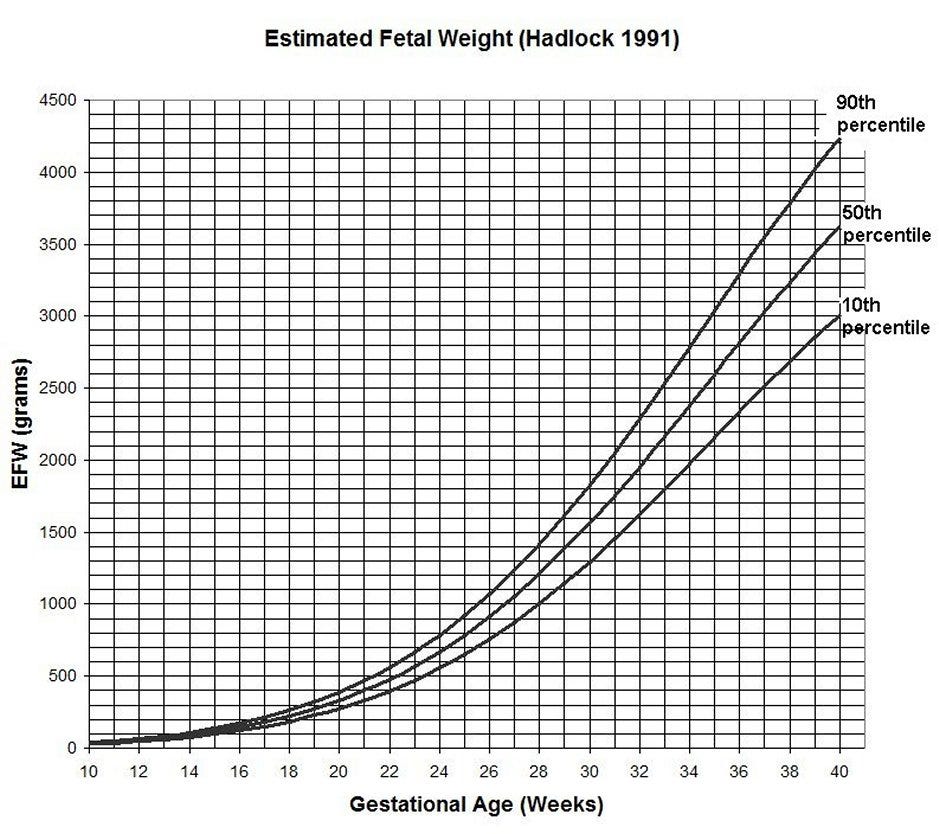

Regardless of the clinician’s suspicion, serial growth ultrasounds can be very helpful. (Note: growth ultrasound should be performed no less than 2 weeks apart) When an EFW falls above the 10th percentile, we aren’t generally worried, especially if they’ve always measured on the smaller side. Consistency of growth is key. If an EFW falls below the 10th percentile, meaning that he is smaller than 90% of other babies for his gestational age, the risk of stillbirth doubles. If an EFW falls below the 3rd percentile, the risk of stillbirth increases even further.

It’s important to point out that 3rd trimester ultrasound is notoriously inaccurate in predicting fetal weight, but the margin of error may be improving with time, so it’s sometimes helpful to measure the velocity of blood traveling from the fetus to the placenta, an ultrasound procedure known as umbilical artery Doppler studies. The same can be done for blood flow within the fetal brain (middle cerebral artery Doppler studies). Abnormalities on any of these studies might open a conversation around early induction of labor.

Abnormal fluid:

Most of the fluid within the amniotic sac is a blend of fluid produced by the baby’s bladder, placenta, and baby’s airways. Assessment of the amniotic fluid volume can be done fairly accurately by ultrasound, and low fluid is known as oligohydramnios.

Historically, two methods have been used to measure fluid: amniotic fluid index (AFI) and deepest vertical pocket (DVP). An AFI consists of measuring the deepest pocket in the four quadrants of the pregnant abdomen. Assessment of amniotic fluid is a part of antepartum fetal surveillance, which we’ll unpack further at the end of this section.

Oligohydramnios is defined as an AFI <5 or DVP <2 cm.

The astute reader might notice a potential conflict: What if an AFI was calculated from the values 0 cm, 1 cm, 1cm, and 2.5 cm? The total is 4.5 cm, which would meet criteria for oligohydramnios diagnosis (<5 cm). But in this scenario there is at least one pocket that is 2.5 cm. This would not qualify for diagnosis of oligohydramnios if the clinician were using DVP instead of AFI.

Researchers have picked up on this as well, and, as it turns out, when we use DVP instead of AFI for assessment of amniotic fluid results in less induction of labor without worse outcomes (e.g. dead babies)

Per the Cochran Group, who reviewed this question in 2008:

“…using the amniotic fluid index increased the number of pregnant women who were diagnosed with oligohydramnios and induced for an abnormal fluid volume when compared with the deepest vertical pocket measure. The women also had a higher rate of caesarean section for so-called fetal distress. Yet the rate of admission to neonatal intensive care units and the occurrence of neonatal acidosis, an objective assessment of fetal well-being, were similar between the two groups. The other measured perinatal outcomes that were no different were a non-reassuring fetal heart rate tracing, the presence of meconium, or an Apgar score of less than 7 at five minutes.”

Before the fluid evaluation, make sure that you are well-hydrated. The sonographer can also scan the baby’s bladder. If it’s full, then fluid levels might rise when your baby urinates. There is no such thing as “low-ish fluid” or “borderline low fluid”. It’s either normal or it’s not. If it’s low, especially if the baby’s growth is restricted, then there may be a problem with the placenta, especially if fluid levels were normal on prior ultrasound.

Hypertensive disorders:

One of the scariest scenarios for OBGYNs, myself included, is the dreaded diagnosis of preeclampsia, which is diagnosed when we begin to see end-organ damage due to “toxemia”.

Entering pregnancy with hypertension is easier to manage, because we expect that blood pressures will drop in the 2nd trimester, then return to the elevated baseline in the 3rd trimester. Hypertension induced by pregnancy, on the other hand, is a little more mischievous.

If blood pressures are ≥140/90 mmHg (either number) on at least two occasions before 20 weeks gestation, then we treat this as chronic hypertension, and anti-hypertensive therapy may be beneficial. If blood pressures are elevated ≥ 140/90 mmHg after 20 weeks gestation, then we see this as a pathology related to the pregnancy, and this is a problem.

The blood pressure elevation alone is sufficient to diagnosis gestational hypertension. When you begin to see protein in the urine or other signs of damage to the kidneys, damage to the liver, or if a pregnancy woman begins to develop widespread edema, upper abdominal pain, insufferable headaches, visual changes, or if blood pressures are sustained in the severe range (160/110 mmHg), then we start to get worried, and it becomes very reasonable to open a discussion around early IOL.

In general, the diagnosis of severe preeclampsia may be met with a recommendation to deliver the baby as early at 34 weeks or even sooner. For gestational hypertension and preeclampsia, IOL is generally recommended as early at 37 weeks. There are always exceptions, but this is why we have the training that we do: we must be discerning.

When any of these conditions - small babies, low fluid, or hypertensive disorders - emerge, especially in combination, the conversation around risks, benefits, and alternatives to IOL must be considered, and various antepartum fetal surveillance techniques are often invaluable. In addition to growth ultrasound, amniotic fluid assessment, and fetal Doppler studies, non-stress testing, biophysical profiles, and Bishop scoring are all helpful tools in coming to a decision with your clinician.

Non-stress testing (NST): monitoring the fetal heart rate by continuous tracing to monitor heart rate variability and the presence/absence of accelerations/decelerations

Biophysical profile: combines NST, DVP, and direct visualization of fetal movement and breathing efforts on ultrasound

We must consider the health of the mother, the well-being of the fetus, the likelihood of successful induction, and the likelihood of a baby having a better shot at thriving if removed from their amniotic universe before the onset of labor.

In conclusion…

IOL rates continue to climb, in part due to the ARRIVE Trial, which is just one study. And if an OBGYN cites this study as a means of reducing our c-section rate, it would be reasonable to counter with: “Aren’t there more reasonable ways to reduce the c-section rate than universal IOL at 39 weeks?”

It’s important to acknowledge that induction of labor is sometimes necessary to assure a living baby, but we also must acknowledge that there are good reasons for which we were evolutionarily predisposed to grow babies for upwards of 42 weeks and birth our offspring vaginally. IOL doesn’t not always solve a problem. More often than not, it’s a cure looking for a disease.

Small babies aren’t always going to die in-utero. Abnormal Doppler studies might influence your decision. The risk of stillbirth also increases if there is low fluid. And it increases further more in the setting of poorly controlled hypertension or unstable preeclampsia. But rarely do the presence of any of these factors alone make for a clear black and white decision. A crystal ball would certainly be welcome when these risk factors begin to appear in concurrence…

It’s simply never very clear which path to take, and the more information that your clinician makes available to you, the more likely you can find a path that feels right to you. None of us wants to be told that “a baby has died and that it could have been prevented by early delivery”, and clinicians should never use language like “your baby might die if we don’t induce”, but we are all human. We are all (hopefully) doing our best.

Stillbirth is many parents’ greatest fear. Mine, too. But given that the risk of stillbirth for all comers between 39 weeks and 39 weeks 6 days gestation is 0.6, per the CDC, there is a much greater chance that your baby won’t die without that induction. A common scenario that I haven’t yet described is isolated olighydramnios, in which fluid is low but there aren’t any other indications for IOL (e.g. growth restriction or hypertensive disease). One systematic review of six studies asking this question found that emergency c-section due to “fetal distress” was increased by over 2-fold in the setting of IOL for isolated oligohydramnios. Are OBGYNs and midwives including this finding in their counseling?

If we truly care about the well-being of birthing women and babies, then we must take all available information into account before jumping the gun. We won’t always guess correctly, but a little discernment can go a long way.

What are the potential hidden costs of our over-reliance on Pitocin®? That’ll be the focus in Part 3.