Oxytocin versus Pitocin®: Induction of Labor and a World Without Love - Part 1 of 3

Induction and augmentation of labor, and a vision of a world without the "love hormone"

In Part 1 of this series, I’ll be focusing on oxytocin and its activities throughout the pregnancy continuum. Part 2 will focus on the increased use of synthetic oxytocin (Pitocin®) in the conventional, hospital-based maternity care model. Part 3 will focus on the potential detrimental effects of the nearly ubiquitous use of Pitocin® in U.S.-based childbirth, considering that 98% or more of birth are happening within hospitals.

This series will take you on a journey. Along this journey, I will hopefully convince you that there is potentially an issue with our high rates of synthetic oxytocin use in conventional obstetrics.

3 key questions inspired this 3-part series:

Is there a difference between endogenous and synthetic oxytocin on the mother, baby, or the dyad?

Can we continue to justify induction of labor without consequence to these players?

Does induction of labor increase the risk of c-section?

At the end, we may have more questions than we started with, without being able to answer the original 3 questions decisively. But that’s ok. This is the point of scientific inquiry. Welcome to the world of nuance, where nothing is black or white.

Part 1

Oxytocin Endocrinology

The hypothalamus is a part of the brain that interacts with the body through a variety of signals to the pituitary gland in order to help the body maintain homeostasis. Sometimes the hypothalamus imparts its effects through direct neuronal input to the anterior pituitary. Other times, hormones are produced in special magnocellular neurons that connect the hypothalamus and the posterior pituitary, and these hormones are released into systemic circulation when needed.

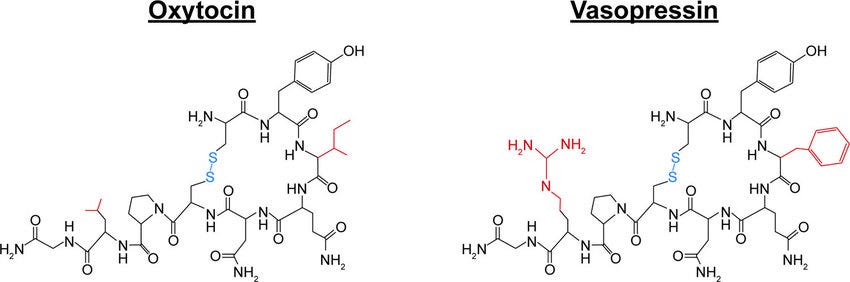

Two such hormones produced and released by this latter mechanism are vasopressin (anti-diuretic hormone, or ADH) and oxytocin. These two hormones are closely related in structure but have generally opposing actions in the body. ADH is a “contracting” hormone; oxytocin is an “opening” hormone. Although the majority of this essay will be looking at pregnancy and childbirth, it’s important to remember that both XY (males) and XX (females) rely on these hormones for maintenance of homeostasis.

ADH

Plays an important role in water reabsorption from the distal portion of the renal nephron as well as vasoconstriction, the combination of which leads to an ↑ in blood pressure

Released from the brain in response to hyperosmolarity (meaning too little sodium) in the blood or a decrease in blood volume of 10% or more

Also released in response to significant stress, including infection

Exerts its vascular effects by binding to receptors in the endothelium lining your blood vessels

Oxytocin

Plays an important role in conception, childbirth, and lactation

Released from the brain when the cervix is disrupted or stretched in a positive feedback fashion

Causes rhythmic uterine contractions during childbirth throughout labor

Stimulates the contraction of myoepithelial cells around lobules in the breast to eject milk into the mouth of a nursing newborn

Plays a role in orgasm and ejaculation

Influences the lower portion of the uterus (not quite the lower uterine segment, as that is developed late in pregnancy) to cause a quivering of the musculature after intercourse to draw sperm up towards the openings of the fallopian tubes

New insights also reveal that oxytocin and ADH affect bonding patterns and stress mitigation. Oxytocin “opens us up” to connection. If this is true, can we expect synthetic oxytocin (Pitocin®) to have the same effects?

Oxytocin, love, and stress

Any discussion around oxytocin falls short without talking about its role in stress mitigation and connection.

With the right setting and circumstances, after sex, especially with orgasm, you immediately feel a sense of connection to your partner. This is in large part due to oxytocin.

But that’s not all. We get a hit of oxytocin when we kiss, when we hug, when we play with our kids, and when we cuddle with our pets. Under the influence of oxytocin, we feel content, safe, and in love. Inside the womb, the baby is eventually encouraged Earthside due to the influence of prostaglandins, cortisol, and oxytocin. When birth unfolds in an undisturbed manner, a baby is born within a sea of oxytocin (love), and they immediately find their bearings in their mother’s arms, hearing their father’s sweet voice, and they are reassured that falling in love with you is part of healthy attachment.

Beautiful, isn’t it?

The issue is that most women are not experiencing undisturbed childbirth. In fact, with 98% of women giving birth in hospitals, very few are even giving birth without synthetic oxytocin.

Fawn, fight, freeze, and polyvagal theory

Let’s take a moment to appreciate the elegance of the nervous system.

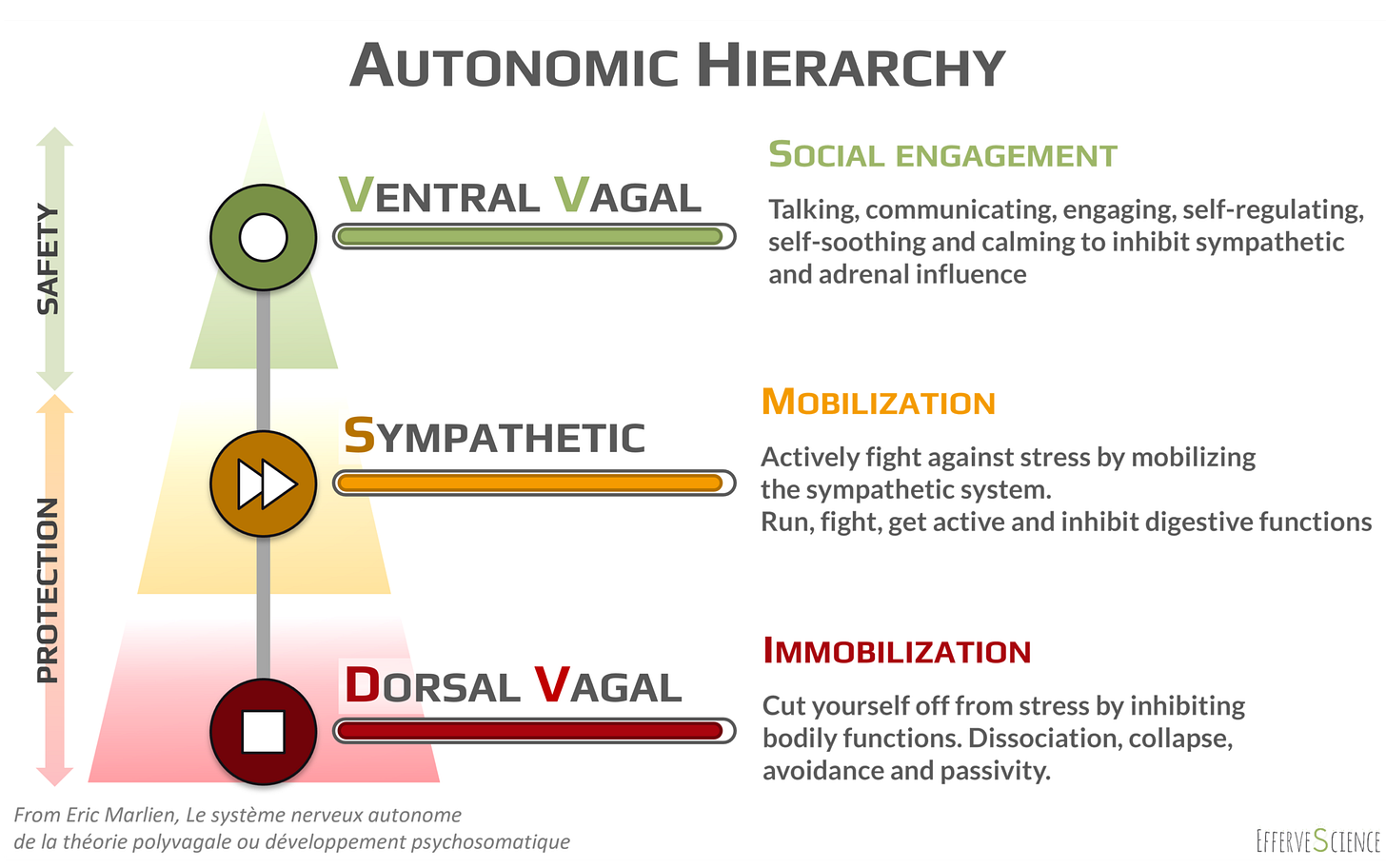

In medical school, physicians learn that there are two branches to the autonomic nervous system (ANS): the sympathetic (SNS) and parasympathetic (PNS) branches. The SNS is the gas pedal (flight, fright). The PNS is the brake pedal (rest, digest). The actions of the ANS are imparted through the vagus nerve, which emerges from the brainstem and runs the length of the body, touching nearly every organ and gland along the way.

As it turns out, there are two major limbs of the PNS: ventral vagal and dorsal vagal. These two limbs innervate tissues above and below the diaphragm, roughly and respectively.

We all know what it feels like to have our ventral vagal system governing our experience: connecting, conversing, kissing. We feel safe. (“Fawn, Fuck”) When we are in this state, physiologic changes signal to others that we can be approached in a social gathering, or that we are open to connecting intimately with our partners.

When we are in a sympathetic state, we are alert. We feel stressed, we are seeking out threats, and we are ready to meet those threats head on. ADH and the catecholamines play a major role in getting us into this alert state. (“Fight, Flight”) When we are in this state, our pupils dilate, our shoulders rise, and we posture ourselves in a way that signals the opposite of safety to potential interlocutors.

Over time, getting stuck in the sympathetic state isn’t great for our health, and we may fall down under the influence of our dorsal vagal system. (“Freeze”) This pattern is also important, though, at times. Rape victims are often criticized for “doing nothing” while under assault, but freezing and allowing things to happen (“playing dead”) can sometimes save your life, especially when followed up with the conscious activation of our ventral vagal system (e.g. smiling or even pretending to be OK with the assault in the moment).

Various situations in life require that each of these three states be accessible, and, in childbirth, it becomes critical that this fluidity is supported. We developed ADH and its receptors earlier in our evolution, which is why the sympathetic state is so easily accessible. It’s reflexive. The ventral vagal pathway is evolutionarily much younger, which is why it’s so hard for many of to access a state of safety and security.

What’s oxytocin got to do with it?

As it turns out, both ADH and oxytocin play a role in stress mitigation.

Per Sue Carter, PhD, who has dedicated her entire illustrious career to the study of oxytocin:

“Oxytocin has particular importance in the face of chronic stress when ‘stress-coping’ effects may take precedence. Oxytocin can facilitate passive forms of coping and protect against shutting down or ‘immobilization with fear’...The capacity of oxytocin to protect this system is critical to the types of social engagements that characterize mammalian social behavior, including birth and parenting.”

- Carter et al, 2020

When a woman is left undisturbed, oxytocin will flood the uterus leading to uterine contraction and eventually the birth of a baby. Catecholamines, which drive our sympathetic state, will increase throughout labor naturally, and you can see relevant changes in a woman’s demeanor when she transitions to the 2nd stage (pushing). At the time that the baby emerges from the vagina, catecholamines will surge to high levels, which is important for the survival of the child (and their mother). But shortly thereafter, the presence of oxytocin supports bonding and co-regulating between the dyad.

There is a concierto of activity within the endocrine system and neurotransmitters that permit this process to unfold. Even though the catecholamines play an important role in child birth, when they are elevated throughout labor, they can have a suppressive effect on the activities of oxytocin. This makes sense when we observe other mammals. When a laboring lioness senses danger in the brush, her labor can stall as a means of affording her time to retreat to safety. Only when she feels safe will labor resume.

For women of our own species, "feeling safe” is far more important than having implements in place to “keep her from dying” while giving birth. When my wife presented to the hospital at 10 cm, she struggled to maintain eye contact with the admissions team. She was unable and maybe unwilling to entertain their hundred questions about medical history (e.g. “Have you ever had a pulmonary embolism?”). She didn’t want to be touched. She wanted the room to be quiet. Only when she felt safe did labor resume. Indeed, only then did she roar out our little Penelope. With less sensory input and questions and the absence of excessive catecholamines, oxytocin was able to take hold once more.

This is why hypnobirthing, water birth, undisturbed birth, and even freebirth are becoming popular. I don’t think it’s because women are merely developing a disdain for interventions; I think it’s also because they aren’t feeling safe in hospitals. And my own clinical experience shows me that the myriad of interventions I was taught to use lead to less gratifying birth experiences.

When oxytocin - and the woman it serves - is left to its own devices, birth unfolds in a beautiful, often more rapid way.

What about the baby?

We aren’t just caring for the birthing woman. As birth attendants, we assume care for the mother-baby dyad. A newborn baby hasn’t fully developed their ANS, and they are literally reliant on their mother (and father) to remind them that they are safe. They don’t have the ability to access their ventral vagal state. They rely on their parents for this.

If you consider how alien the world must be perceived by a newborn, this transition could potentially scare them to death if not for their mother holding them on their chest, letting the baby hear their heart beat, listening to the sweet nothings of their parents…

When you imagine the typical hospital experience, the cacophony of sound, the many people rushing in and out of the room, the needle sticks, the eye goop, and other distractions to the co-regulation of a mother-baby dyad that you’ll find in most maternity suites, it’s perhaps less of a leap to see birth as far more than a medical procedure and pregnancy as more than a disease begging medical intervention. Again…a baby needs to “feel safe”, not to be handled roughly even if in the name “keeping them alive”. This is often a delicate balance.

Perhaps the lack of this opportunity for co-regulation is also a major contributor to sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) among preterm infants, who are forced to spend weeks or months in an incubator, without any semblance of safety or grounding.

Oxytocin and stress mitigation

Oxytocin appears to play a role in mitigating stress, which is a fancy way of saying remaining fluid between the three limbs of the ANS.

“…oxytocin levels were exceptionally high in women with a history of trauma who showed a pattern of dissociation, supporting the hypothesis that elevations in oxytocin can be adaptive in trauma...oxytocin, in part through effects on the vagus nerve, has direct and indirect effects on the immune and metabolic systems across the lifespan. These actions also help to explain the lasting effects of early emotional experiences on physical health and well-being...”

- Carter et al, 2020

This provides some food for thought when we consider the higher risk of nearly every chronic disease or pregnancy complication in women of color giving birth in the United States. When we don’t feel safe, our health unravels, which isn’t a surprise given, as I’ve already mentioned, that the vagus nerve has an influence on virtually every organ in our body. A resistance to oxytocin at the receptor level might be worthy of study as an underlying etiology for these differences.

Males and females may also have differences in their response to oxytocin.

From animal studies, we have found the following:

Administration of low dose oxytocin in pregnancy down-regulates vasopressin receptors in many areas in the brain in both male and female prairie voles (relaaaax, connect with your parents, little baby!)

However, increasing doses of oxytocin in young male prairie voles may lead to more aggressive behavior in adulthood (protection!)

Female prairie voles appear to have a greater tolerance to higher levels of oxytocin without exhibiting aggressive behavior

(References: Bales et al, 2007; Carter et al, 2020; Stribley et al, 1999)

This may explain why men are able to create social bonds even under extreme stress, whereas women have a greater likelihood of “shutting down”. This could be why men in the delivery room can appear to be collected in their advocacy against medical interventions while under duress and yet still find themselves able to connect with their new bundle of joy. On the other hand, many of us men develop this capacity for aggressive advocacy on the part of our birthing partners by virtue of having been flooded with oxytocin and the resulting connection to our mothers in the womb and shortly after birth.

This is all speculation, of course, but it sure as heck makes it harder to simply accept that the majority of women who give birth in the hospital will be exposed to exogenous Pitocin®. From this perspective, hospital policies and procedures could be seen as affronts to the release of endogenous oxytocin from the birthing woman’s brain.

If flooding a baby with oxytocin is the goal then why is there any argument against Pitocin®? Don’t we want the baby to be flooded by the “love hormone”? Who cares if it’s synthetic?

Baby steps…

In conclusion…

Oxytocin is made in the brain and is certainly very important in childbirth, which is why a synthetic version is such a fashionable target in modern obstetrics, but oxytocin has far more actions in the body than uterine contraction. Are we neglecting the beauty of the “love hormone” if we continue to support the rising rate of labor induction?

How did we get here in the first place? When is IOL potentially helpful?

These questions will be answered in Part 2.

Fab read! Our bodies are built with all the tools required for birth then, isn’t all the meddling purely for “speed”? Why is birth constantly rushed? Who does pictocin really serve? It points more to the provider than the mother to me…